Journal of Futures Studies, Dec. 2020, 25(2): 35–48

Applying the Futures Wheel and Macrohistory to the Covid19 Global Pandemic

Phillip Daffara, Principal, FutureSense, PO Box 1489, Mooloolaba, Queensland 4557, Australia

* Web Text version of each JFS paper here is for easy reading purpose only, for the valid and published context of each article, please refer to the PDF version.

Abstract

This paper investigates the systemic impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic and experiments with using two foresight methods with different time horizons to broaden the exploration. The Futures Wheel of consequences is applied to the global shock and pandemic of COVID-19 to firstly analyse systemic impacts of the virus within a short to medium timeframe. Then, four macrohistorical models are applied, to time two probable future trajectories resulting from the bifurcation point of the pandemic. The conclusion provides: (1) insights on the methodology of integrating the Futures Wheel and Macrohistory and proposes that they are indeed complimentary if a common spatial scale is used to link them, and (2) that the city is a practical and effective spatial scale to integrate the methods and their systemic impacts, and (3) real world actions in response to the pandemic, at the scale of the city, that may require further research.

Keywords: Futures Wheel, Systems Thinking, Anticipation, Action Learning, Agility, Adaptive Capacity, Macrohistory, COVID-19

Introduction

The Futures Wheel of Consequences (FW) is an old tool in the strategic foresight toolbox. As an architect I first learnt the Futures Wheel in 2001 in a local government leadership workshop conducted by Sohail Inayatullah. The method was first conceived by Jerome C Glenn in 1971 to visualise the direct and indirect future consequences of a change or event. (Futures Wheel, 2020). I concede that in the suite of futures studies tools, the FW is not a method I practice often with stakeholders and I have often overlooked for other methods such as creative visualisation, scenario development and casual layered analysis.

Might this be the same within the futures studies field in general? A search of the Journal of Futures Studies database created one citation for an article that used the FW, compared to twenty-eight citations for macrohistory. Macrohistory, I believe is a more difficult method to grasp and use with participants compared to the FW.

The reason for the apparent downturn in the application of the FW, may be found within the inherent bias of timescales in each tool. The FW focusses on direct and indirect impacts in the short to medium term, handy for strategic planning. The general understanding within the Futures Studies field is that the FW is a tool that fits within the second pillar of futures thinking – anticipation (Inayatullah, 2008, p. 8). As such it may not challenge or generate alternative futures which are needed to transition out of the Anthropocene. Macrohistory (Galtung & Inayatullah, 1997) in contrast focusses on vast, intergenerational timescales to glean socio-cultural patterns and their diverse implications to anticipate long futures (Daffara, 2004a, p. 22). Within the Futures Studies field it is a method within the third pillar of futures thinking – timing the future (Inayatullah, 2008, p. 10).

So, is it possible to use both futures methods and integrate the systemic implications of the COVID-19 pandemic to encompass both short- and long-term time scales or horizons? The Futures Wheel of consequences is applied to the global shock and pandemic of COVID-19 to firstly analyse systemic impacts of the virus and identify risks and opportunities from the arising future possibilities. The benefits of the FW wheel process draw on a recent Australian case study. Secondly, the weak signals from the Futures Wheel are contextualised using macrohistorical models to time two probable future trajectories resulting from the bifurcation point of the pandemic. Causal Layered Analysis (CLA) then synthesises the multi-dimensional implications of COVID-19 gathered from the FW and Macrohistorical analyses to illustrate the different systemic focus of each method and the significance of this hinge period in human and planetary history.

FW Case Study – Tasmanian Leaders Inc.

In a time of shock and crisis, such as the current global pandemic, decision makers need to respond quickly to impacts in a rapidly changing multifactorial environment. The FW tool comes into its strength during a time of global shock when quick responses are required within short time frames to anticipate possibilities. So why the FW in a time of shock? It is very quick to learn and simple to use by participants. The FW provides clarity on possible courses of action for the short to medium term with future consequences. In a time of shock where decision makers may be overwhelmed the FW provides a brief pause to suspend the biological flight or fight response that may lead to reactionary and poor decisions and allow instead considered responses.

On 26th March 2020, FutureSense hosted a 90min webinar with 25 cross-sector leaders as part of the Tasmanian Leaders Inc program, teaching them how to use the Futures Wheel of Consequences to anticipate the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic virus on their businesses, sector or organisation. The leaders came from various sections including emergency services, cultural, not-for-profit, tertiary education, transport and energy. Angela Driver, General Manager of Tasmanian Leaders Inc., summed up the group feedback: “participants left the session feeling more connected, resilient and resourced. Three things that they are going to need to draw on over the coming months.” (personal correspondence, March 27, 2020).

In preparing the FW workshop, I found that the most recent innovations to the FW methodology had occurred in the design thinking field. The methodology had been enhanced by overlaying the STEEP1 categories to the wheel of consequences to ensure a multiplicity of contexts are explored (Behboudi, 2019). Embedding the FW within different stages of the design process is another more recent development (Fig. 1). It can help in the initial stages when scanning for opportunities or later in the design process exploring how a solution may unfold. “It [FW embedded in a design process] is most useful when done with all stakeholders in the room, as it can also serve as a highly effective decision-making tool” (Behboudi, 2019).

Fig. 1: Futures Wheel in the Design Process, From Behboudi, M. (2019) Futures Wheel, Practical Frameworks for Ethical Design

Main Arguments

From the Tasmanian Leaders case study three main arguments are evident and are presented next.

Context Specific Futures Wheel Applications

The FW workshop presented a generic global FW of possible consequences due to the COVID-19 pandemic, to demonstrate how to generate first, second and third order impacts through “what if” questioning. The adaptive capacity to climate change research, recognises generic and context specific determinants to adaptive capacity (Smith, Carter, Daffara, & Keys, 2010). Applying this to the FW methodology, the consequences generated by the FW can also be characterised as being generic or context specific. To leverage the benefits of the FW process and to build the adaptive capacity to change within participants, it is critical that participants apply the tool to their specific context. This raises their awareness of the systemic implications to their organisation, business or locality, rippling out from the initial shock of a global pandemic.

In the workshop, participants applied the FW individually to their specific context and then shared consequences within breakout groups to see if patterns emerged. Written feedback gathered from participants when asked what they learned when using the FW included2:

“Exploring some of the aspects of STEEP that may have been de-prioritized in the face of economic impacts”.

“Complexity and interrelation rather than linear cause-consequence relationship”

“Process for systematically breaking down a complex problem”.

“Cool new tool and method to think through a complex situation and extract some useful observations regarding risks and opportunities which can be used to take action against”.

“Using the [STEEP] categories to break down a problem”.

The written feedback shows how the FW with the STEEP framework facilitates multi-factorial consequences to be mapped which leads to systemic critical thinking of possible futures. That is, the search for interrelations between impacts, across social, technological, environmental, economic and political dimensions, not just casual linkages within a dimension.

Generic Futures Wheel COVID-19 Risks and Opportunities

The generic implications of a global pandemic relevant to most contexts and jurisdictions are presented in the COVID-19 Pandemic FW (Fig. 2). Three rings radiating from the core event represent the first order, second order and third order consequences. The outer field contains fourth order impacts and more. In addition to the five STEEP categories, a sixth segment allows “open space” for the mapping of other implications and in this case psychological implications emerged as a significant dimension related to a global pandemic. I stress that the mapped impacts are generic and far from complete. However, it illustrates the complexity and the critical systems thinking required to respond holistically to a pandemic. More important is the need for stakeholders (in this case everyone on the planet) to apply futures thinking using the futures wheel to their own context-specific circumstances and life conditions.

After the consequences are mapped, stakeholders can identify impacts that pose risks or opportunities to their specific context (place, organisation, business etc.). Next, I discuss a handful of causal lines of consequence that contain significant risks and opportunities.

Fig. 2: Covid-19 Pandemic Futures Wheel Generic Impacts, Daffara, P. Tasmanian Leaders FW workshop Presentation, 26th March 2020

Opportunities

Smart cities

To contain the pandemic, certain countries have employed digital technologies to manage the crisis. Taiwan is using big data by integrating “national health insurance, immigration and customs databases, generating data to trace people’s travel history and clinical symptoms.” (The Straits Times, 2020). South Korea has employed similar digital technologies to enable real time spatial mapping of COVID-19 cases (Coronamap.site) based on extensive testing and tracking of visitors and citizens and to trace sources of the virus. (Nature, 2020). The Australian government intends to rollout Singapore’s TraceTogether digital application to help trace COVID-19 contacts within communities to refine local lockdowns if required (The Guardian, April 19, 2020). No doubt, proponents for increased surveillance of the public health of populations, referred to as bio-surveillance, see the relationship between smart city innovation techno-systems and public health emergency responses. Innovations include the mining and analysis of urban sewers to monitor pathogens, virus loads and other indicators of health (e.g. drug use, alcohol consumption) to trace viral outbreaks (Senseable City Lab, 2019; The Guardian, 2016). Smart City advocates argue that “Innovative smart city technologies such as the Internet of Things (IoT), artificial intelligence (AI), 5G, open data, and analytics, offer the potential for cities to respond to the pandemic more effectively.” (Chan & Paramel, 2020).

Smart Cities acting as place-based digital bureaucracies are well positioned to integrate datasets and resources to maintain public health and contain future viruses where poverty and digital divides are not major obstacles within the jurisdiction. Smart cities are not a panacea for poverty, inequality, urban apartheid, social polarisation, digital divides and urban fragmentation caused by capitalism and the informational, networked society. (Castells, 1999).

Relocalisation

Place-based lockdowns to contain the spread of the COVID-19 virus (e.g. Wuhan) effectively shut down non-essential production, which resulted in the disruption of global supply chains, particularly for medical equipment. The opportunity for the world, post COVID-19 is to design and create resilient supply ecosystems (Entrepreneur, 2020), going beyond the application of technologies within the current ecosystem, to drive a relocalisation of production and distribution. If Australia can use 3D printing technology to produce ventilators or surgical visors in a crisis when supply is constrained, why not always?

The relocalisation movement seeks to disrupt the globalisation of capital and production of food, materials and services, reducing the ecological footprint of human activities and building community resilience to future shocks (Hines, 2000).

Ecological regeneration

The great pause to the economies of the world to contain the COVID-19 pandemic through the lockdowns and home isolation of half the world’s population have yielded beneficial environmental impacts. A reduction in CO2 and pollution has been observed due to the drastic drop in road and air transportation; and manufacturing.

First China, then Italy, now the UK, Germany and dozens of other countries are experiencing temporary falls in carbon dioxide and nitrogen dioxide of as much as 40%, greatly improving air quality and reducing the risks of asthma, heart attacks and lung disease. (The Guardian, April 10, 2020)

The unexpected shock of the virus and the speed with which governments reigned in their respective economies, with resultant ecological benefits, provides an opportunity for perception change within communities. A glimpse of what a zero-carbon world may yield in terms of collective wellbeing and resurgent, resilient ecosystems. “The unthinkable has become thinkable” (The Guardian, April 10, 2020). Rather than a return to business-as-usual:

UN leaders, scientists and activists are pushing for an urgent public debate so that recovery can focus on green jobs and clean energy, building efficiency, natural infrastructure and a strengthening of the global commons. (The Guardian, April 10, 2020)

Risks

The opportunities presented through a scaling up of digital capability for smart cities were previously discussed in respect to public health. The leap in the digital delivery of other services due to the pandemic such as work from home, online learning for schools, mental health support, telehealth, entertainment and creative arts and online shopping are evident in post-industrial, “informational networked societies” (Castells, 1989, 1996). Two risks emerge from the FW analysis.

Homecentredness

Firstly, the phenomenon of ‘homecentredness” anticipated by Castells (1996, p. 398) has the potential to escalate during physical and social distancing measures and drastically impact daily home life and ultimately the urban-social contract. A pandemic forces people to retreat to their homes and rely on digital technologies to maintain many aspects of their work-life habits. What I call hyper-homecentredness leads to chronic social isolation and loneliness, poor socialisation within communities and poor mental health outcomes. The health impacts of loneliness are manifold and well researched:

The risk of premature death associated with social isolation and loneliness is similar to the risk of premature death associated with well-known risk factors such as obesity, based on a meta-analysis of research in Europe, North American, Asia and Australia. (Holt-Lunstad, Smith, Baker, Harris, & Stephenson, 2015 cited in Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2019)

How many indirect deaths will occur due to the health impacts of social isolation and loneliness compared to the direct deaths of the virus?

The risk or prolonged forms of social isolation until a vaccine is available for the COVID-19 virus is that the enforced banning of and cessation of cultural events, festivals, sports, public gatherings and even protests may erode the public life, identity and spirit of cities, towns and communities. The conveniences of (1) home-based consumption; (2) the digital interconnectedness of devices; and (3) the delivery of products and services to the home enabled by the smart city; may also increase individualism, further straining the sense of belonging to a larger community.

Digital blackouts

Secondly, the ICT risks of digital platforms not having the system capacity to cope with the surge in demand are significant. Take for example the failure of the Australian Government’s Centrelink online Jobseeker registration site within their MyGov platform to deal with the possibly, one million newly unemployed citizens caused by the pandemic’s lockdown laws (The Guardian, March 24, 2020).

A worse scenario to contemplate is the internet going dark whilst the pandemic is still forcing geographic lockdowns, thereby not only physically distancing people but also socially disconnecting them from work based and personal networks. Cyber-attacks against critical platforms are a possibility during this pandemic’s health crisis and economic deep freeze, adding a new dimension to the chaos that would unfold. Are we prepared for this risk, either from state-based cyber terrorists or anarchistic hackers?

Mental health risks

The FW clearly plots the causal line of consequences that ultimately impact a communities’ mental health and wellbeing. Starting with lockdowns and social distancing measures, to mood shifts, increased isolation and loneliness, increased stress within families, the loss of hope and the likely increase in domestic violence and suicides. These probable impacts are well documented in a recent mental health study conducted in the countries that experienced the early outbreak of the COVID-19 virus, before a global pandemic was declared by the WHO. (Brooks, Webster, Smith, Woodland, Wessely, Greenberg, & Rubin, 2020).

Related to mental health issues are the psychological factors that underpin the wellbeing of a community. Mainly poor messaging by governments on what to do and why, with a resultant loss of hope. The implications of loss of hope will be discussed in more detail next, in the context of macrohistory.

The litany level: summing up of the futures wheel analysis

The application of the FW of consequences to the COVID-19 pandemic, at the litany level of discourse, challenges the political messaging of governments and chief medical officers, that this virus is mainly a public health and economic emergency. Rather, the COVID-19 pandemic is a whole of systems crisis, as it impacts or disrupts multidimensional qualities of life as shown in the STEEP categories. At the system’s level, I am reminded of Ian Lowe’s model of transition from the pig-face systems model of sustainability to the nested systems model (Lowe, 2016, p. 230) (Fig. 3). The dominant systems worldview today is the pig face, where the economy remains the dominant concern. Leaders responding to this pandemic need to be reminded that the environment and society are not here to serve the economy (like two little ears on a pigs face), but rather that the economy is to be designed to care for our society, cultures and environment (like nested spheres). Bluntly, responding to the COVID-19 pandemic is an opportunity to redesign our economies to better serve our socio-ecological systems. But this opportunity is too daunting for most global leaders who seek a return to economic normalcy and its dominance as soon as possible.

Fig. 3: Transitioning sustainability models at the worldview level, Adapted from Lowe (2016, p. 230) The Lucky Country? Reinventing Australia

Weak Signals in the Context of Macrohistory

This part, seeks to contextualise the weak signals that emerge from the FW of a global pandemic using macrohistory and cycles of cultural change. I call the future possibilities, weak signals, because they emerge as 4th or 5th order consequences in the FW from the initial shock. As such, they normally would be beyond the awareness of participants and stakeholders. These weak signals are then contextualised using macrohistory to make some sense of the epochal shifts triggered by a pandemic. I will refer to the macrohistorical models of Sorokin, Toynbee, Teilhard de Chardin and Khaldun (Fig. 4).

A Post-COVID-19 Worldview – Creative Destruction?

From Sorokin’s macrohistorical perspective, the COVID-19 pandemic is both precursor to and trigger for a global depression and ecological chaos that exposes the weaknesses of the materialistic (sensate) cultural paradigm, holding up the mirror to the limits of growth, consumption, wealth and comfort. “If everyone is out to satisfy material needs there may not be enough to go around, and particularly if nature’s needs are to be respected” (Galtung & Inayatullah, 1997, p. 117). A grab-what-you-can mentality emerges – like people rushing into supermarkets worldwide to horde toilet paper and food – to bunker down in self isolation.

This sets the scene for a renewal phase from chaos to a new spiritual (ideational) cultural paradigm, motivated by the push forces of self-disgust “and with how the human condition has degenerated into nonhuman and even antihuman absurdities. There are also the pull forces, longing for steering and guidance” (Galtung & Inayatullah, 1997, p. 117). Including the observed environmental spinoffs caused by the pandemic’s great pause on production and human activity, such as cleaner air, water and return of wildlife to cities (The Guardian, March 23, 2020, April 10, 2020). This possible ideational renewal may be underwritten on green and humane values, but we need to look to other macrohistorians to understand the cultural dynamics needed to motivate the creative leap from chaos to a shared universal spirituality.

Let us look to Toynbee, Teilhard de Chardin and Khaldun with a touch of Pink3 to speculate the importance of a creative culture to respond to the global pandemic.

Toynbee’s macrohistory makes the point that a civilisation grows and reproduces itself through the challenge – response – mimesis (CRM cycle) by the efforts and capability of a creative minority (Galtung & Inayatullah, 1997, p. 122). Sorokin’s quantum leap back to an ideational-spiritual worldview requires Toynbee’s cultural creatives to tell a unified transformative narrative to inspire the masses to contemplate a different type of planetary civilisation. Likewise, Pink’s ‘conceptual age’ (2005, p. 48) that focusses on human empathy, story and design is relevant to provide push and pull factors for a post COVID-19 worldview that resets our sense making and memetic reproduction of meaning.

Teilhard de Chardin’s “research for a synthesis overcoming the dualism of matter and spirit” (Daniela Rocco Minerbi in Galtung & Inayatullah, 1997, p. 105) is at the centre of his macrohistory. This synthesis and unity of knowledge mirrors Sorokin’s idealistic cultural mentality, that integrates material concerns with those of ideas and metaphysics. Teilhard’s process of personalisation and complexification towards ‘noogenesis’ and the ‘noosphere’, is an evolutionary stage of planetary culture and collective consciousness and reflection reliant on the transpersonal growth of the individual. This evolution is driven by a cosmic tendency:

Towards the spirit – towards pure radial energy (love). He recognises the continual tension of the universe towards increasing entropy (disorder) within his model, and that at times the socialisation process (noogenesis) is counter-evolutionary. When this happens, society succumbs to entropy, individualism and depersonalisation, and falls away from the spiritual. (Daffara, 2004a, p. 15)

As illustrated in the FW analysis, the risk here is that the worldwide government responses to socially isolate communities to contain the global pandemic, fuels individualism and depersonalisation. Conversely, it could be argued that this decline and psychological challenge is necessary for Sorokin’s and Toynbee’s regeneration process.

Fig. 4: Macrohistories and COVID-19 in Context, Synthesised from diagrams in Galtung, J. & Inayatullah, S. (Eds. 1997)

Khaldun’s macrohistory and the concept of asibiya provides key ingredients to Teilhard’s emergence of the noosphere through noogenesis. Put simply without the philosophical jargon: “For Khaldun, what is important in transformational leadership is asibiya – the collective purpose, unity and memory that binds a group.” (Daffara, 2004a, p. 25). The implication here, is that a post COVID-19 world and cultural paradigm or zeitgeist, requires the bottom-up co-design of a collective purpose and vision to enrol the peoples of this planet into a resilient social-ecological system.

All the above macrohistorians point to the importance of using this great global pause to reset what it means to be human, why we do what we do on this fragile planet, and how we might do better. In short, how might we design alternative futures, not so vulnerable to the cascading shocks and consequences of a global pandemic mapped by the FW.

Causal Layered Analysis: Summing Up the Macrohistory Analysis

I use Causal Layered Analysis (CLA) (Inayatullah & Milojević, 2015) as a method to summarise the FW and macrohistorical analysis so far. Previously, I have discussed the litany and systems level implications of the FW of consequences to the COVID-19 pandemic. What follows next are the worldview and myth/metaphor levels of reality. Table 1 illustrates all levels related to only two perspectives – the bifurcated choice in this hinge period in human history triggered by COVID-19.

The application of macrohistorical models to the COVID-19 pandemic, reinforces the critical importance of Western societies to respond to the systemic emergency with an awareness of cultural change dynamics. At the worldview level, we need to transition from a ‘growth is good” cultural paradigm to ‘positive development with zero growth’ (Daffara, 2004b). The pandemic reminds us of the urgent need to avoid ecological collapse and regenerate our built and natural environments. In terms of ‘timing the future’, macrohistory shows that COVID-19 comes at a critical time with other converging stressors – social, environmental, economic and political. COVID-19 may be the final systemic shock or tipping point, defining a ‘hinge period in human history’ (Inayatullah, 2008, p. 11). A period of bifurcation between contrasting probable futures. Either humanity will respond creatively to reset our values and design and build more resilient Lifeworlds in harmony with the planet, or we risk further ecological, social and political decline and disintegration. At the myth/metaphor level of reality, each contrasting future may be aptly described by Khaldun’s macrohistory (Galtung & Inayatullah, 1997. p. 28-29): ‘unification with kindness’ for and by team humanity verses ‘fragmentation with loss of hope’ with the masses monitored and controlled by powerful and wealthy plutocrats of the informational, networked society.

Table 1: CLA of the hinge point in human history from COVID-19

| Decline and Disintegration | Creative Renewal | |

| Litany | COVID-19 is a public health and economic emergency. We will make decisions to return to economic normalcy as soon as possible. | COVID-19 is a whole of systems emergency. We will take this opportunity to make decisions to remake a just, caring society. |

| Systems | Pig face sustainability model:

The economy is dominant and is served by our natural resources and social capital. |

Holonic, nested model of sustainability. The economy cares for our cultures and societies and natural global commons. |

| Worldview | ‘Growth is Good” cultural paradigm | ‘Positive Development4 with Zero Growth’5 |

| Myth using Khaldun’s macrohistory

Author’s Metaphor From Nature |

‘Fragmentation with loss of hope’

Teams of Plutocrats Muddy ponds |

‘Unification with Kindness’

Team Humanity Blossoming lotus |

The above CLA of only two probable trajectories at the bifurcation point of COVID-19 is intentional to focus the attention of decision makers and stakeholders. To use Toynbee’s macrohistory, either civilisations commit to slow ‘suicide’ or creative renewal (Galtung & Inayatullah, 1997, p. 122). The system and worldview levels draw from Lowe’s perspective (2016) and Atkisson’s work (1999) respectively. The myth level uses Khaldun’s macrohistory to contrast the story of fragmentation versus unification. At the metaphor level, Toynbee’s macrohistory provides the disintegration narrative where “the Creative Minority becomes a Dominant Minority trying to control the Internal and External Proletariat [wage-earners]” (Galtung & Inayatullah, 1997, p. 122). What I have labelled as “Teams of Plutocrats” exerting power and influence over governments and peoples, for example, through their internet based informational networks. In contrast, the metaphor of “Team Humanity” speaks for itself in the unification trajectory.

I have sought to synthesise the CLA of each trajectory and present an underpinning metaphor from nature to evoke an emotional response within readers. I propose that the futures are like muddy disparate ponds versus a riparian system that supports blossoming lotus. If we make the collective choice towards transformation and creative renewal, then diverse alternative futures within that overarching trajectory ought to be explored using the full suite of foresight technologies.

Fig. 5: Contrasting Metaphors of the collapse versus creative renewal probable futures, Drawn by P Daffara (2020)

Conclusion & Further Research

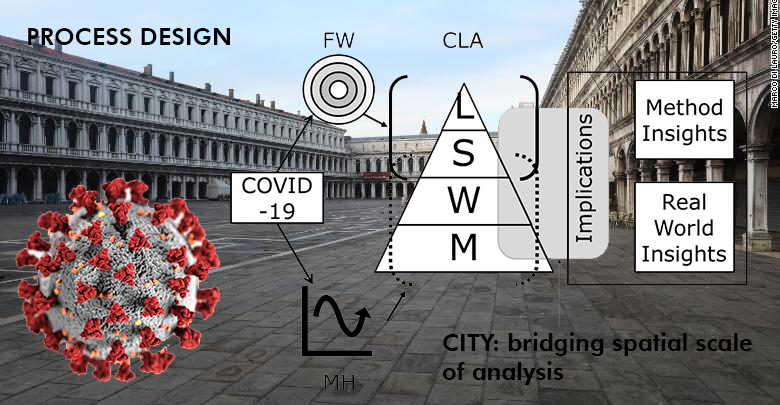

The following findings are offered from the FW and Macrohistorical analyses of the systemic impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic (Fig. 6). Designing a foresight process using two foresight methods with different time horizons, does broaden the exploration of impacts. The integration of the FW and Macrohistory, becomes more meaningful if a common spatial scale of analysis is used to link them. In this study, a spatial scale of analysis was not predetermined. However, during the process, the city emerged as the relevant spatial scale of study, able to link the different time scales of each method in a complimentary way and their arising systemic impacts.

Fig. 6: Study Process and Integration of Findings, Drawn by P Daffara (2020)

Methodological Insights

FW is a quick tool to grasp, giving leaders the agility to respond rapidly in the COVID-19 global pandemic as well as anticipate consequences down the causal line and their possible risks and opportunities. During the FW analysis, at the systems level, several 4th and 5th order impacts emerged, that highlighted the importance of the city in responding to the pandemic. For example: (1) relocalisation of supply chains, (2) the capacity of smart cities to trace and isolate cases and facilitate digital social connectivity, and (3) ecological renewal due to the lockdown of cities. It was found that the city could be used as a common spatial scale to provide the means of integrating the FW and Macrohistorical analyses – assisting in sense making – across CLA’s different levels of reality.

As a result, the second part of the conclusion also provides real world actions in response to the pandemic at the scale of the city, and proposes areas of further research.

CLA helped to synthesise the multi-dimensional implications of COVID-19 gathered from the previous analyses and illustrates the significance of this hinge period in human and planetary history.

CLA also illustrates how the technique of the FW focusses the attention of stakeholders and participants on the litany and systems levels of reality in response to COVID-19. Whilst the comparative analysis of macrohistories draws out worldviews, cultural paradigms and myth/metaphors that influence civilisational change in response to the pandemic. The application of CLA provided a means of synthesis for making sense of the levels of reality for the two probable futures post COVID-19.

Real World Insights

Firstly, how do we allow a planet of 7.8 billion people to collectively grieve the losses caused by the global pandemic? How do we as a creative minority (futurists/foresight practitioners) initiate the co-design of planetary asibiya – collective purposes and visions to transition towards a more ideational, integrated culture that values wisdom over technical knowledge?

Secondly, sources of hope are critical during this crisis to motivate the inner growth and personalisation of individuals as described by Teilhard and drive Toynbee’s socialisation or mimesis between cultural creatives and the masses to counter Khaldun’s loss of asibiya (collective purpose and vision).

Thirdly, I offer a practical path forward to respond to the second and third points mentioned previously, to be implemented at the spatial scale of the city or town. This links back to the FW impacts affecting smart cities and the relocalisation of communities and their economies. Cities are agents of change (Daffara, 2011) each a specific socio-ecological system responsible at a territorial scale for providing pluralistic, diverse futures. I propose that cities are best positioned to engage their citizens to grieve the losses caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, through truth telling fora and to facilitate personal and collective healing. Rather than erect monuments to memorialise the crisis overcome, it would be better to initiate city foresight projects to create shared values and visions for the alternative ways forward. The purpose is to create post COVID-19 “City Noospheres” – creative, learning and diverse city cultures (Daffara, 2011. p. 685) with greater adaptive capacity and resilience to respond to the next epidemic and other wicked challenges that persist such as the climate emergency and ecological destruction caused by human activity (The Guardian, March 25, 2020).

Summing up the application of the FW of consequences to the COVID-19 pandemic at the litany level of discourse, challenges the political messaging of governments that this virus is mainly a public health and economic emergency. Rather, the COVID-19 pandemic is a whole of systems crisis that presents an opportunity to redesign our economies to better serve our socio-ecological systems and the human values that underpin them.

Summing up the application of macrohistorical models to the COVID-19 pandemic, we find that we are at a hinge period in human history, critically important for Western societies to respond to the systemic emergency with an awareness of cultural change dynamics. Will the human species reset during this great pause and unite with kindness or fragment with loss of hope?

Notes

- STEEP: social, technological, environmental, economic and political categories used to describe multi-factorial issues within a system.

- Each quote listed from the written participant feedback represents a comment from a different workshop participant.

- Daniel Pink is not recognised as a macrohistorian, but his model of world change provides a useful evolution of ages. He does not provide references or sources for his synthesis, so I continue to cite Pink as the author of the “Conceptual Age” in which we currently operate in.

- Positive Development, developed by Janis Birkeland (2008) requires that our development must be positive, adding back to the planet’s ecosystem services in every project. It demands more than nett zero carbon.

- Zero Growth, as discussed by Alan Atkisson (1999, p. 24–26) in this systems’ view, civilization must transform itself toward “Development without Growth”, away from the current course of “Growth equals Development”. This is, in his view (which I share), the greatest challenge of our generation and must become humanity’s fundamental project for the 21st century (Daffara, 2004b).

References

Atkisson, A. (1999). Believing Cassandra, Carlton North, Australia: Scribe Publications.

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. (2019, September 11). Social isolation and loneliness. Retrieved from https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/australias-welfare/social-isolation-and-loneliness

Behboudi, M. (2019). Futures Wheel, Practical Frameworks for Ethical Design. Retrieved from https://medium.com/klickux/futures-wheel-practical-frameworks-for-ethical-design-e40e323b838a

Birkeland, J. (2008). Positive Development, London, UK: Earthscan Press.

Brooks, S. K., Webster, R. K., Smith, L. E., Woodland, L., Wessely, S., Greenberg, N., & Rubin, G. J. (2020). The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: rapid review of the evidence. The Lancet, 395 (10227), 912–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30460-8

Chan, B., & Paramel, R. (2020). Smart cities & public health emergency collaboration framework: Meeting of the minds. Retrieved from https://meetingoftheminds.org/smart-cities-public-health-emergency-collaboration-framework-33446?mc_cid=e1c88de2b3&mc_eid=a902b5de1b

Castells, M. (1989). The informational city: Information technology, economic re-structuring and the urban-regional process. Oxford, Blackwell.

Castells, M. (1996). The rise of the network society, the information age: Economy, society and culture, Vol 1. Oxford, UK: Blackwell.

Daffara, P. (2004a). Macrohistory and city futures. Journal of Futures Studies: Epistemology, methods, applied and alternative futures, 9(1), 13-30.

Daffara, P. (2004b). Sustainable city futures. In S. Inayatullah, (Eds.), The Causal Layered Analysis (CLA) Reader: Theory and case studies of an integrative and transformative methodology (pp. 424-438). Taipei, Taiwan: Tamkang University Press.

Daffara, P. (2011). Rethinking tomorrow’s cities: Emerging issues on city foresight. Futures, 43, 680–689.

Entrepreneur. (2020). COVID-19 Will Fuel the Next Wave of Innovation. Retrieved from https://www-entrepreneur-com.cdn.ampproject.org/c/s/www.entrepreneur.com/amphtml/347669

Futures Wheel. (2020). Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Futures_wheel

Galtung, J., & Inayatullah, S., (Eds. 1997). Macrohistory and macrohistorians – perspectives on individual, social and civilisational change. Westport, U.S.A: Praeger.

Hines, C. (2000). Localization: A global manifesto. London, UK: Earthscan.

Inayatullah, S. (2008). Six pillars: futures thinking for transforming. Foresight, 10(1), 4-21. DOI 10.1108/14636680810855991

Inayatullah, S., & Milojević, I. (2015). CLA 2.0: Transformative research in theory and practice. Tamsui: Tamkang University Press.

Lowe, I. (2016). The lucky country? Reinventing Australia. Brisbane, Australia: University of Queensland Press.

MIT Senseable City Lab. (2019). The Underworlds Book. Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Retrieved from http://underworlds.mit.edu/

Nature. (2020). South Korea is reporting intimate details of COVID-19 cases: has it helped? Retrieved from https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-020-00740-y

Pink, D. H. (2005). A whole new mind, moving from the information age to the conceptual age. Crows Nest, Australia: Allen & Unwin.

Smith, T. F., Carter, R. W., Daffara, P., & Keys, N. (2010). The nature and utility of adaptive capacity research. Report for the National Climate Change Adaptation Research Facility, Gold Coast, Australia.

The Guardian. (2016, March 27). The MIT lab flushing out a city’s secrets. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/science/2016/mar/27/lab-that-flushes-out-city-secrets-massachusetts-mit-senseable-lab-sewage

The Guardian. (2020, March 13). Anxiety on rise due to coronavirus, say mental health charities. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/mar/13/anxiety-on-rise-due-to-coronavirus-say-mental-health-charities

The Guardian. (2020, March 23). Coronavirus pandemic leading to huge drop in air pollution. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2020/mar/23/coronavirus-pandemic-leading-to-huge-drop-in-air-pollution

The Guardian. (2020, March 24). Newly unemployed Australians queue at Centrelink offices as MyGov website crashes again. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2020/mar/24/newly-unemployed-australians-queue-at-centrelink-offices-as-mygov-website-crashes-again#maincontent

The Guardian. (2020, March 25). Coronavirus: ‘Nature is sending us a message’, says UN environment chief. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/mar/25/coronavirus-nature-is-sending-us-a-message-says-un-environment-chief

The Guardian. (2020, April 10). Climate crisis: in coronavirus lockdown, nature bounces back – but for how long? Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/apr/09/climate-crisis-amid-coronavirus-lockdown-nature-bounces-back-but-for-how-long

The Guardian. (2020, April 19). Australia’s coronavirus contact tracing app: what we know so far. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/apr/17/australias-coronavirus-contact-tracing-app-what-we-know-so-far

The Straits Times. (2020, March 13). Coronavirus lessons for the world from ground zero of Asia. Retrieved from https://www.straitstimes.com/asia/east-asia/coronavirus-lessons-for-the-world-from-ground-zero-of-asia