Journal of Futures Studies, March 2020, 24(3): 105–112

Science Fiction as Moral Allegory

Timothy Dolan, Policy Foresight, 1258 Munson Drive, Ashland, Oregon, U.S. Tel.: 1-541-499-5593

* Web Text version of each JFS paper here is for easy reading purpose only, for the valid and published context of each article, please refer to the PDF version.

Keywords: Science Fiction, Ethics, Classic Science Fiction, Influences on Futures Studies, Popular Science Fiction

Introduction

An extraordinary amount of science fiction (SF) carries significant content of a moralistic nature consistently reflecting concerns about social becoming nested within the context of the times the works were written (Blackford, 2017). As a rule it is perilous to lump an entire genre into any single orientation, but in the case of SF and ethics there are strong connections especially in the classic works familiar to the general public. It makes a lot of sense when one considers that ethics is much about consequences and SF is much about illuminating them.

“Moral literature” is a term likely to set off associations with various scripturally based “just so” stories, often written for children as digestible lessons in the faith, or as with Aesop’s fables, intended to carry explicit principles of human relations. These tales were explicitly meant to justify existing conventions as well as highlight key social principles. The favored genres of this literature are fable and apologue through which the normative world is justified in contradistinction to parable (“It has been written, but I say unto you…”) and satire; which are the genres of subversion.

Layered over this stratum of edification literature were the now archaic studies in character development that held popular attention in the 18th and through to the early 20th century. These were exemplified in the works of Charles Dickens, and in America through the Horatio Alger stories. These coincided with a strain of “muscular Christianity” that manifested itself in both the YMCA and Boy Scouts in response to the societal consequences of concentrating large numbers of young men in the manufacturing centers where drunkenness, gambling and prostitution were corroding civilization itself in the eyes of the churchmen of the day. These series relentlessly pressed the theme of triumph over adversity. Weakness of the flesh rigorously suppressed through sport was also a well-worn theme persisting well into more recent times as this author recalls arguments in favor of school athletics programs for males as a means to dampen sexual impulse. Thus this moralistic literature was much shaped as a response to industrialization and its resulting initial in-migration of young single men.

These emphases on moral virtue would wax and wane as industrial urbanism began to mature and new mediums were introduced. A kind of dialectical struggle for hearts and minds would play out in the early 20th century with the rise of the novel. The novel itself as a literary form had a reputation for titillation in the eyes of the straight- laced, but its broad popularity determined that titillation might be okay if it was well written by, say, a D.H. Lawrence. In Europe surrealism and the explosive works of Sigmund Freud would mark the contradictory shadow side of imperial order, and rigid rationality that marked a wide swath of Western Europe from Victorian London to Vienna. Ultimately it would be World War I that would bring the biggest challenge to moralist apologue. Overtly ambivalent novels began showing up in the works of the likes of Fitzgerald, Hemingway, Orwell and Steinbeck that gave voice to the random nature of human experience and fate independent of character both good and bad.1

Then there were the cinematic treatments of moral themes generally framed as cautionary tales to justify the popular bourgeois sentiments largely in reaction to the near pornographic period of movie making in the early 1900s (Grievenson, 2004). The cinematic flipside of Horatio Alger were the gangster films of the 1930s and 40s becoming somewhat more refined in the Film Noir genre of the 1940s and 1950s. The standard Noir theme involved some poor male (the “sap” as known in the nomenclature of the day) falling for an evil “dame” who would prove to be the undoing of them both. While the message of Horatio Alger was the affirmation of the Protestant work ethic, Film Noir demonstrated the violent dark-side consequences of yielding to temptation and taking both material and carnal shortcuts.

Science fiction as Ethical Instruction

An important caveat moving forward is that the “science fiction” referred throughout this piece is the genre as popularly perceived. “Literature” is also broadly drawn to include numerous film productions both cinematic and for television. This is also not science fiction as sometimes defined by literary scholars. To this point is the case of Jules Verne, who is conventionally seen as an early science fiction writer reflecting a popular view that is disputed by Verne scholar William Butcher, 2005. He points out that Verne’s books almost never contain any innovative science whatsoever, but merely extended known technologies, like the submarine and rocketry, beyond the limitations of their day. However, projection of the present is a key feature of most science fiction. In that regard, at least two of his most prominent works, 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea, and Journey to the Moon, might qualify at least nominally as science fiction though the latter work is now relegated to space fantasy.

There are many familiar industrial era writers like Mary Shelly (Frankenstein), and Robert Lewis Stevenson (Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde) that some see as straddling the fuzzy boundaries of genre. For instance, Frankenstein simultaneously described as a gothic novel and the earliest work of science fiction (Aldiss, 2005). They are in the science fiction genre for having an unambiguous moral content stamped into their work that ran counter to the scientific optimism that was de rigueur among the intelligentsia of that time. The message of unease over the mischievous potential of rogue science leading to abominations had common cause with the character literature that ran contemporaneously with it.2 The impulsiveness of Prometheus, and the recklessness of Icarus are recapitulated in Shelly’s as well as in Robert Lewis Stevenson’s main character.

In similar fashion, the next generation of classical SF writers, H.G. Wells, Aldous Huxley, and his Eton pupil, Eric Blair (aka George Orwell), would also emerge to transform the genre by infusing it with more overt dystopian social commentary. Their overarching messages were of deep skepticism over the technological optimism embedded in modernism. This ranged from genetic and pharmacological manipulations in Brave New World, and The Island of Dr. Moreau, to the pernicious potential of collective mind control and the prospect of television to watch us in 1984, which anticipated our entanglement in the “world-wide web” by several decades. Their com- mon vehicle for expressing concerns over the then present-day prospects of their respective societies was that of allegory. The use of allegory was a splendid hook to engage serious literary elites in speculative projection that was not simple fantasy, but spoke to very real and very rising trends.

H.G. Wells personified ambivalent contrasting futures as with the utopianism of The Shape of Things to Come and the dark projections of The Time Machine, and his prescient concerns with genetic manipulation in The Island of Dr. Moreau. Wells was an especially seminal figure in exploiting the tensions between utopian and the dystopian. Yet echoes of consequence for human transgression goes back to Gilgamesh, Genesis, Homer and Dante. He is also arguably the progenitor of Futures Studies as an academic discipline, arguing for establishing “foresight” in university pedagogy (BBC 4, 2019)3.

A final note about Wells and the use of SF as social allegory manifested in The Time Machine where he presents a vision of a system so polarized as to manifest two species, the refined, elegant, pastoral but passive, almost bovine bubble culture of the Eloi; and the brutish literal underclass of the Morlocks who feed on the flesh of the beautiful but thoroughly domesticated prey. It was allegorical critical commentary on the aesthetic movement of late 19th century England that promoted art for art’s sake promoted by the likes of Oscar Wilde. One can perceive presnt-day parallels in the rise of “Hipsterism” and the reactions of a resentful working class that would metaphorically like nothing better than to eat these influencer wannabe-trust fund babies.

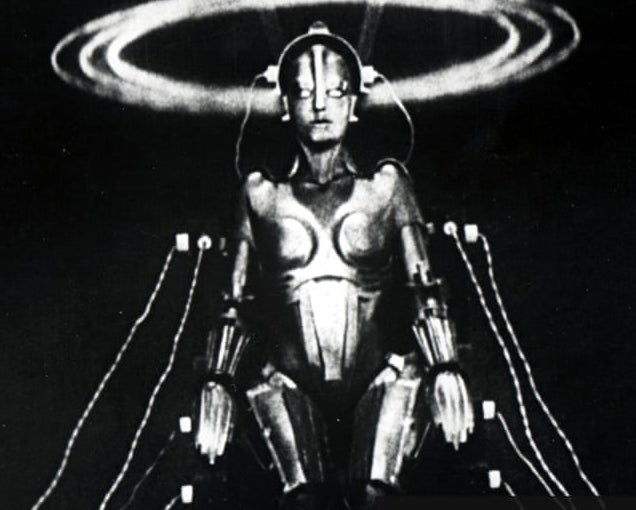

The rise of feature film heralded a new means to project contemporary angst into SF casings. The earliest and arguably most influential for its day was Fritz Lang’s magnum opus, Metropolis (1927) that captured that critical period between the World Wars when political polarization in Germany split the nation between Bolshevik Marxism-Leninism and rising NAZI nationalism. It is a model for SF moral allegory in projecting 1927 to 2027 and extrapolating class tensions to a remarkably accurate portrayal of high-tech mechanization manifesting impressive urban landscapes, but at the cost of the misery of workers. It is a lesson in how the gap between the top 1 percent literally on top and rest would lead to profound conflict. Lang was not at all nuanced in his use of Christian metaphor with the film’s apex-corporatist father “Joh” (a German play on “Jehovah”) being very Old- Testament in his determination to hold power. The film’s heroine, “Maria” (literally a virgin mother as caretaker for the workers’ children) would meet and love-smite Fredor, the son of Joh and from their unlikely encounter launch his romantic quest where he would encounter and then take on the trappings and suffering of his fellows complete with a magnificently stylized crucifixion scene. An iconic mad scientist complete with gloved hand (a stock prop in all subsequent evil genius stereotypes) would create an AI/android clone of Maria, purposefully designed (by Lang) with asymmetrical eyes to convey the imperfection of all human artifice. The real Maria, kidnapped to create the imposter, would predictably be rescued, but the fake would incite the masses to violent revolution, who did not realize until almost too late, that they were to flood their own abodes and in so doing kill their own children (a not unsubtle message by Lange who was ever the bourgeois moderate trying to find a humane middle path to reconcile the classes. Hardly anyone knows the intent of the movie now as much of it has been lost to poor preservation. Yet, almost everyone has seen the images with the film’s special effects, which are still amazing 93 years later.

Fig. 3 is especially chilling for its coincidental resemblance to the Holocaust made more apparent when the full scene is observed. This uneasy relationship with the industrial era and the persistence of often very gross social inequities is a running theme that is with us to this day. Bringing moral and ethical guidance to historical process is a powerful theme in SF, especially in its popular classical corpus of works.

The mid-twentieth century generation of SF writers would elaborate on this thread, led by Isaac Asimov and his Foundation Trilogy and his “I Robot” corpus, the latter core element being a robotic ethical code, “The Three Laws of Robots”. Arthur C. Clarke’s works were more about science writing, very much representing a kind of therapeutic technological optimism, HAL 9000, and his “treaty” with Isaac Asimov notwithstanding (McAleer, 1992). When he did venture into the transcendent moral theme such as in Childhood’s End, (1953), it was through the trope of encounter with advanced alien forms that were wisely not over described, but transcendently beneficent in overall tone. Clarke did more than write morally informed SF. He famously testified against the Reagan administration’s “Strategic Defense Initiative” (SDI) in the early 1980s earning him the wrath of program proponent Robert Heinlein. Ray Bradbury, another eminent writer of popular science fiction of that generation, was often identified as intensely moralistic (Bloom, 2010). Even Frank Herbert, author of what is often considered to be the greatest science fiction novel ever written, embedded a deep ecological sensibility in the tapestry of Dune (Cappel, 2012). The movie Avatar (2009) would invert Dune’s environmental thread with a plot in which an Eden was about to become a wasteland whereas in the Dune, a wasteland would become, at least ecologically, an Eden.

Fig. 1: Selected Iconic Images from Metropolis

Fig. 2: Fredor’s Stylized Crucifixion from Metropolis

Fig. 3: Fredor’s Vision of Mass Slaughter in Service to Industrialism

Both works were allegories with Herbert particularly prescient is envisioning exploitation of an essential resource (spice as petroleum) in a desert place (Arrakis as Iraq) leading to a messianic uprising by the indigenous “Freman” (The quest to establish a caliphate in all its forms).

Then comes the problematic Robert Heinlein. Robert Heinlein, was viewed by many as holding the most dubious of moral codes, yet it turns out that he did hedge his near Ayn Randian views according to Wight, 2005:

Robert Heinlein, who strenuously insists that “selfishness is the bedrock on which all moral behavior starts” completes this same sentence by noting that such behavior” can be immoral only when it conflicts with a higher moral imperative” (2004). Hence, he explicitly acknowledges that a higher moral imperative exists, and sometimes must be operative.

Heinlein grudgingly acknowledged a “higher moral order” that trumps the radical individualist views he was known to espouse. While acknowledged as one of the “big three” of mid-to-late 20th century SF writers (with Asimov and Clarke) his approach did not deal with issues of social justice or “right conduct” in any meaningful way and his work is thus an anomaly to the prevailing connections between SF and ethics.

The other noteworthy element of the moralistic strain of the science fiction genre is how much of it has been driven by the Anglo-American tradition, quite likely because being at the cutting edge of technological invention for much of the past century alerted its literati to its perils. Sensitivity to the consequences flowing from innova- tion is supported beyond the Anglo-American perspective. There is Japanese science fiction led by Godzilla and its variants, almost all of which rooted in the horrible mutations that came from exposure to nuclear radiation, of which the people of Japan had first-hand experience. Marxist/Leninist socio-economic determinism undergirding the Soviet project would generate a cadre of writers who would use science fiction to mask their critique of that ideology (World Futures Studies Federation, 1986). First among the Soviet SF was Yevgeny Zamyatin’s We, (1921), often cited as the touchstone for dystopian SF.

The fear of extra-terrestrial invasion, a theme first brought to the public imagination by H.G. Wells in The War of the Worlds (Hughes and Geduld, 1993) would later be resurrected in a classic 1938 radio broadcast that unintentionally resonated with the American public’s skittishness over the rise of fascist militarism. This fear of the foreign ideological other bent on invasion would yield bastard spawn with the rise of the Cold War. After all, Anglo Americans had visited policies of displacement and extermination, mostly by exposure to disease, on the native peoples of North America, and thus had a collective unconscious terror of the same fate for them. In a remarkably ironic twist, Well’s had turned that fear on its head by having the invaders die off from exposure to the microbes instead of visa versa.

The crude alien-invasion kitsch of B-movie Hollywood that fed on the Red-scared American imagination of the 1950s into the mid-1960s made that sub-genre an easy premise to sell. This was especially true to a tide of baby boomer teens looking for visceral thrills of what were more monster movies than science fiction proper. To the extent that there was any edifying messages, they were either proto-environmental with portrayals of the consequences of our pollution, nuclear and otherwise, assaulting nature and having its mutant minions reeking vengeance in return, or appeals to unify in the face of larger external threats echoing the allied response to Axis predations, Soviet containment, United Nations idealism, or good old human xenophobia.

In the midst of the tabloid made-for-teens fluff of pop SF, a classic would emerge in the American film The Day the Earth Stood Still (1951), a thinly veiled appeal for universal demilitarization that resonated well beyond the generation that first viewed it. The undergirding theme of seeking to understand the “other” was in a grand tradition of SF that goes all the way back to Shelly’s Frankenstein. In this, it again provided instruction that harkened back to the fates of scriptural prophets and even messiahs that contradicted the attitudes of their times to later earn vindication. What made this movie particularly impressive was its clear confrontation over the prevailing attitudes of those times that were resolutely hostile to that most alien of threats to Americans, the two headed monster of Stalinism and Maoism.

Well over a decade later would come, via the television screen, and the next prophet of social justice in the person of the American writer and television producer, Rod Serling, and most incisively in his Twilight Zone television series. He was very much the contrarian but in every sense one based upon a moralist perspective.

Serling’s deeply held sense of social justice infused his scripts often set beyond of this world’s time and space (a literal “Twilight Zone”) with political and social allegory not seen since Orwell. Serling’s work coincided with the social upheavals of the 1960s and the moral questions showcased in his series mirrored the times. Civil rights, social alienation, the manipulative power of fear, the Vietnam War, the early space program, were all addressed as moral issues under the veneer of science fiction.

The next wave of popular television SF was Roddenberry’s Star Trek. It’s first incarnation only lasted 3 seasons, but perhaps even more than Serling, shaped a generation in its view of frontiers, both still existing and being a mixed bag of beneficent discovery and unambiguous threat. It’s tropes were, in fact, quintessentially American as a futuristic version of the old west with cowboys and Indians, outlaws and settlers. Its bastard offspring Battlestar Galactica was likewise seen to have emulated the themes of classic westerns. (Porter, Lavery, & Robson, 2008).

The climatic model of SF allegorical film that seemed to forecast the current rise of xenophobia (It has always been around in either latent or active) was Blade Runner. Here the xenophobia was reframed as “terraphobia” insofar as the humanoid “replicants” were consigned to off-world exile to do the dirty work of their progenitors. The core moral issues addressed in this now classic film derived from a novel by Philip K. Dick is an articulate treatment of a well-established SF trope concerning what it is to be human. In this it aligns with those earlier clas- sics like Frankenstein and the Island of Doctor Moreau. The movie itself also makes use of Christian metaphor where the arguably most favored son replicant returns to confront his father, killing him in frustration over his mortality. The final scenes have him saving and forgiving the man who was pressed into killing him and his kind. The use of eyes (windows to the soul) were also a constant presence throughout the movie.

A key point regarding the moral dimensions of science fiction is that it often rises to the level of classic literature because it exposes the contradictions of prevailing norms in its investigation of the moral ambiguities that arise from the socio-technological nexus. These include such themes as genetic engineering, surveillance societies, AI, space exploration, and again, what it means to be human. In this there is a resonance with many of those drawn to futures studies where finding normative contradictions and anticipating the transformations that come from them is a vital part of the field. Good science fiction is never about building utopias as much as about warning of the dystopias seeded in their attempt. So too is the implicit charge of the futures studies/foresight communities to explore alternative structures and processes are employed towards its end. “Justice” is of course, part of the moral amalgam with “honor”, “responsibility”, and “wisdom” being three other ingredients with other values that might be added to individual cognitive taste. “Freedom” is a trace element. At best it’s the freedom to choose futures wisely. The timeless lessons of consequence to innovations and policies over the long-term exemplified in classic SF is thus a useful and even essential resource in foresight/futures studies.

Virtue (moral sensibility by another name) is not an antiquated relic of Confucian-Greco-Christian thought though the word itself might be seen as such. The sentiment persists in deep in the cultural ether and invoked in other ways. This is evidenced by its high “cited by” metrics on Google Scholar for works like MacIntyre, 2013; (26,321 as of April 30, 2019 + 1 with this author’ s reference) that deals with the question of what is described as “after virtue”. One can reasonably intuit that in an age of institutional and ethical compromise at the highest levels of government seemingly all over the world, there is a countermovement arising. It is led by the likes of first-year congressperson Alicia Ocasio-Cortez, the barely-teen environmental activist Greta Thunberg, and still teenage gun control advocate and Parkland High School mass shooting survivor David Hogg among the countless other advocates for human dignity worldwide. As foresight/futurists, we would do well to maintain a moral compass as our work may come to make a difference in the coming inflections of humanity and its anticipated variants.

The moral dimensions of SF provide guardrails, or better, highway lane reflectors that the high beams of foresight illuminate as historical process moves at ever greater velocities, and thus to ever greater risks. A rising generation of activists have exposure to the moral underpinnings of SF, if only through the complex storylines in the Marvel Universe cinema and the better multiplayer gaming platforms that require mutual cooperation and trust in scenarios that challenge the lure of expediency. It is in this sense that as the paradigm of religion holding a monopoly over ethical conduct has morphed, first by Enlightenment and now popular SF visions.

Futurists, particularly those involved in public policy areas, would be well served to be cognizant of the influ- ences of SF and its metaphors in the Causal Layered Analysis (CLA) sense. They are useful points of departure for imagining and implementing alternative futures. In this Inayatullah’s work in anticipatory action learning is a useful guide (Inayatullah, 2005; 2006). Given that SF tends to examine themes in a form of storytelling that throws the socio-technological nexus into a critical light, often removed from current time and space, its ability to break out of convention and go to the mythic levels of discourse makes it a unique literary genre. More then that, however, is its capacity to consider and develop the moral dimensions of these alternatives. Without such considerations there is a risk of drift towards a mindset to engage in practices simply because they can be done without rigorous review of potential consequences. After all, nearly every technological innovation has either been first developed or subsequently found military applications. The military implications of technology are one strain of SF, but only one. Larger societal and even deeper cultural alternatives are another rich vein to mine with an eye less towards achieving a homogenous preferred future, but as ethical guidance in the quest to create preferred futures justice. SF may not be the only moral literature left but the best of it is that.

Notes

- Except for the comeuppance of Jay Gatsby in Fitzgerald’s magnum opus, it is notable that the banal ignorance that come of privilege in the person of Daisy got away scot (pardon the pun) free.

- A useful primer on the relationship between science and literature is Clarke, B., & Rossini, M. (Eds.). (2010). The Routledge companion to literature and science. Routledge.

- Pay particular attention to the bonus segment of the “Time Machine” podcast at about the 49-minute mark where he is quoted as appealing for developing a university pedagogy in “foresight”.

References

Aldiss, B. W. (2005) “on the origin of species: Mary Shelley”. speculations on speculation: theories of science fiction. eds. James Gunn and Matthew Candelaria. Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow.

BBC Radio 4, (2019), In Our Time, “The time machine”, (Broadcast and Podcast) https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/m0009bmf (Retrieved, November 28, 2019)

Blackford, R. (2017). Science fiction and the moral imagination: visions, minds, ethics. Springer.

Bloom, H. (2010). Ray Bradbury. Infobase Publishing.

Butcher, W. (2005). Hidden treasures: the manuscripts of” twenty thousand leagues”. Science Fiction Studies, 43-60.

Cappel, R. (2012). Science fiction is a humanism: the “open universe” ethics of Frank Herbert’s Dune. Crisis, 75, 71.

Clarke, B., & Rossini, M. (Eds.). (2010). The Routledge companion to literature and science. Routledge.

Grievenson, L. (2004). Policing Cinema: Movies and Censorship in Early-Twentieth-Century America. Univ. of California Press.

Hughes, D. Y., & Geduld, H. M. (1993). A Critical Edition of The War of the Worlds: HG Wells’s Scientific Romance. Bloomington: Indiana UP. p. 1.

Inayatullah, S. (2006). Anticipatory action learning: Theory and practice. Futures, 38(6), 656-666.

MacIntyre, A. (2013). After virtue. A&C Black.

McAleer, N. (1992). Arthur C. Clarke: The Authorized Biography. Chicago, Contemporary Books.

Porter, L. R., Lavery, D., & Robson, H. (2008). Finding Battlestar Galactica: An Unauthorized Guide. Sourcebooks, Inc..

Wight, J. B. (2005). Adam Smith and greed. Journal of Private Enterprise, 21(1), 46.

World Futures Studies Federation, IX WFSF World Conference & General Assembly: Who Cares? – And How? (conference proceedings) Honolulu, Hawaii, May 1986.

Zamyatin, Y. (1993). We. 1921. Trans. & Intro. Clarence Brown. New York: Penguin Books.